Adventures in 3D printing PVC - Finale

11 May 2023Finally, printing with liquid PVC

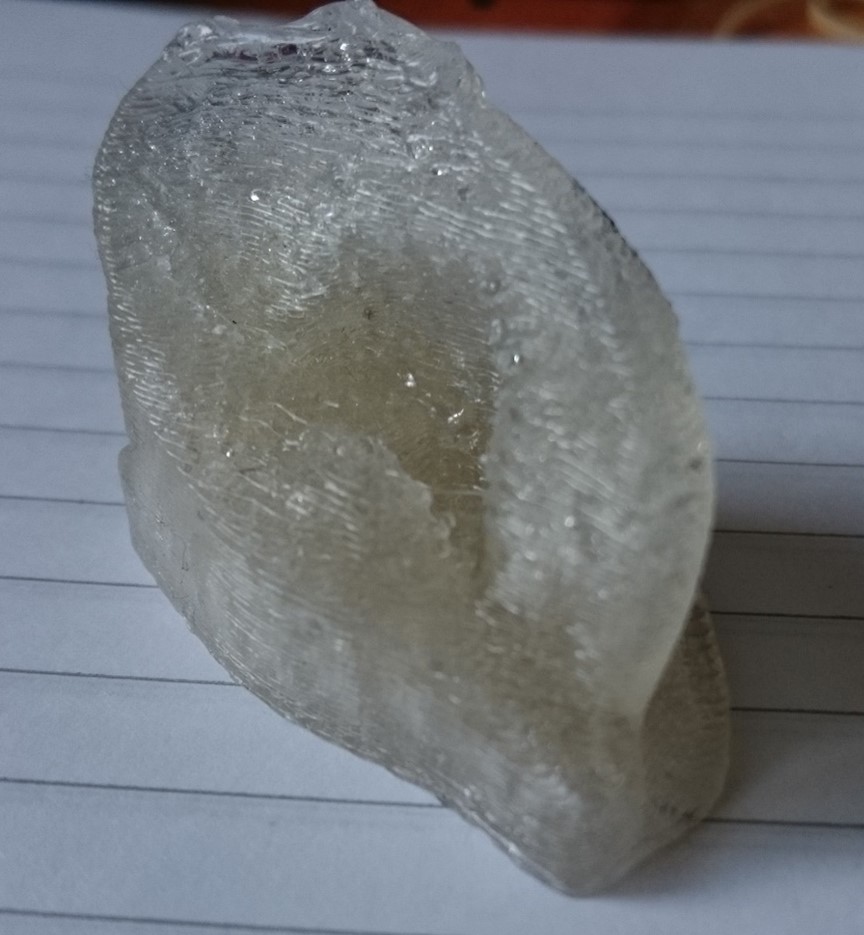

With these three main issues as well as pump calibration out of the way, it was possible to truly begin 3D printing with PVC, at first beginning with very simple shapes such as flat pucks with a 5cm diameter and 3mm thickness such as the one pictured below:

These pucks are well suited to detecting any telltale signs of 3D printing issues, such as gas inclusions, over or under extrusion or bad feed system calibration. Fortunately, the system worked extremely well with the aforementioned improvements, and it was possible to print a more complex demo piece: a scaled-down model of a human ear:

Comparison of 3D printed PVC with conventionally manufactured PVC

The final of the initial three goals of the project was to compare the PVC produced by the 3D printer with PVC that had been conventionally manufactured, i.e. cast PVC.

Due to time and equipment constraints in CIT at the time, it was only possible to perform a tensile test as a comparative metric, as there are no Shore hardness testers in the college.

ISO 37:2011 – Rubber, vulcanised or thermoplastic – determination of tensile stress-strain properties

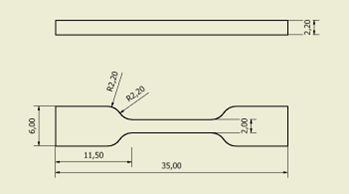

ISO 37 describes methods for testing the tensile properties of elastomers by destructive testing in a tensile testing machine. It provides two main methods of testing: using ring test pieces or dumbbell test pieces. Due to the comparative ease with which dumbbell test pieces can be manufactured, it was decided to use the latter.

Dumbbell test pieces

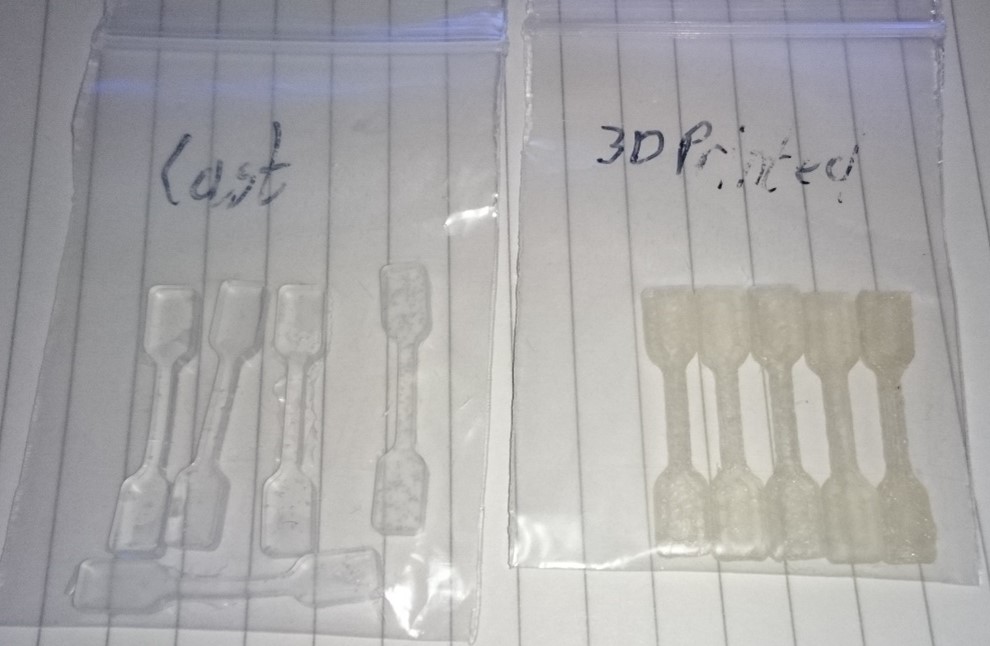

The standard prescribes four different sizes of dumbbell for use in different scenarios, however due to the limited quantity of PVC on hand, type 4 dumbbell geometry was selected

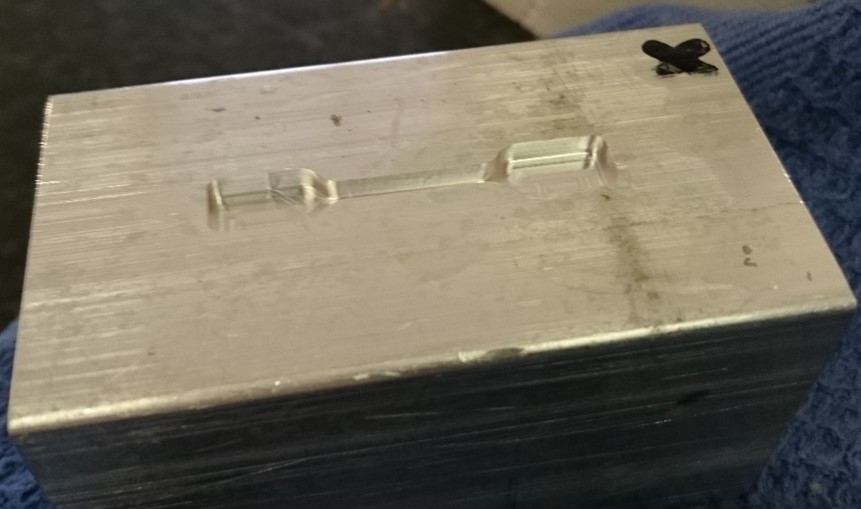

To manufacture the cast test pieces, a mould was built from a spare piece of aluminium stock using the CNC milling centres in CIT. A solid model of the mould was transferred to a workshop computer running AlphaCAM. A toolpath was created to mill out the exact geometry required, and a piece was produced (pictured below).

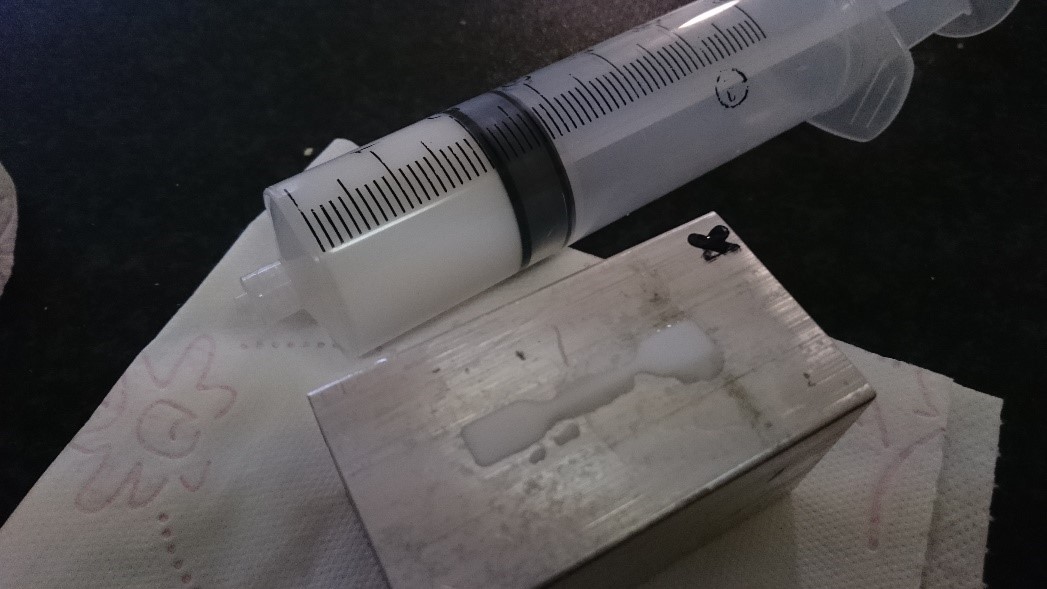

The moulds were filled with PVC using a syringe to dispense the right quantity of PVC, and then placed in the oven at 250°C where the PVC was allowed to cure until glassy, a colour change which indicates that the right curing state of the PVC has been reached.

At the same time, the PVC 3D printer produced five samples of 3D printed PVC dumbbells of the same geometry, also printed at 250°C, in order to obtain a one-for-one comparison.

The resulting samples:

Tensile testing

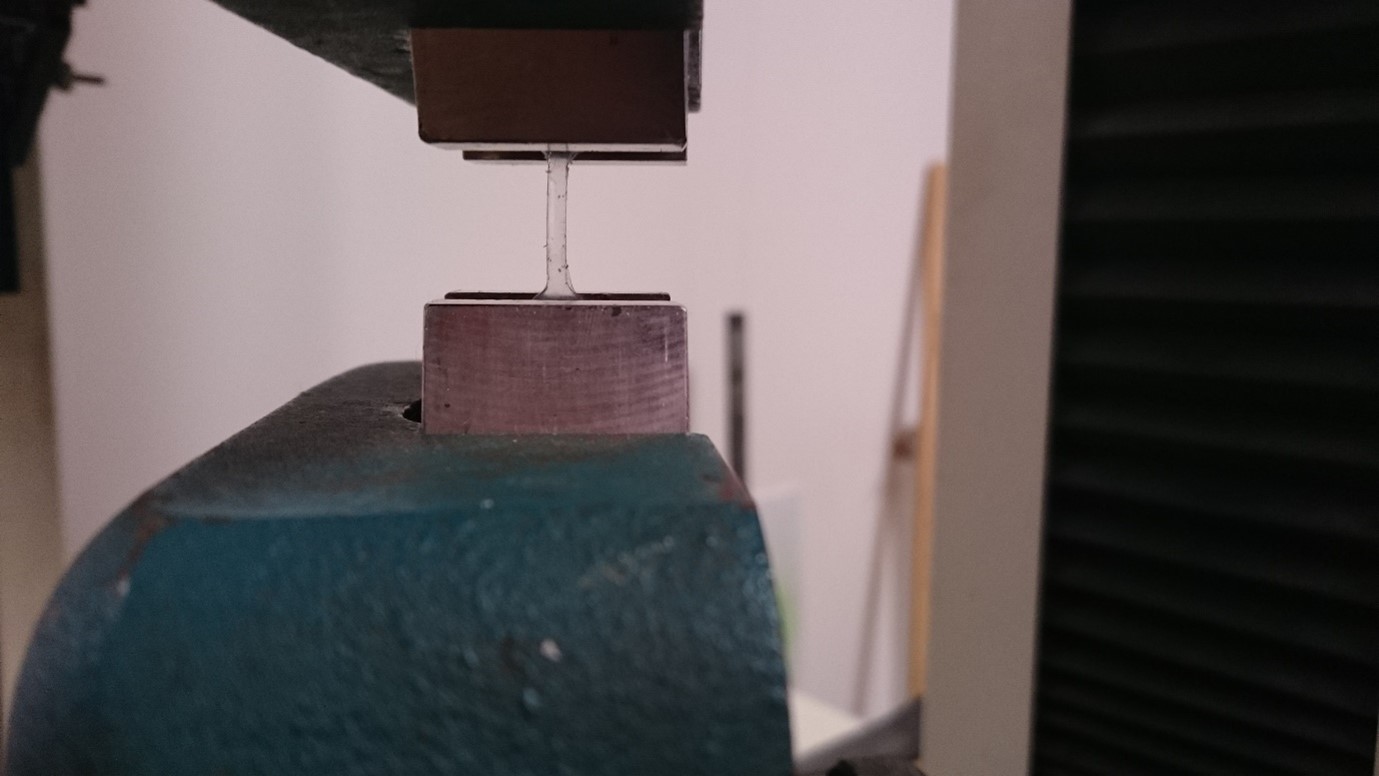

The testing was carried out on the Instron tensile testing machine in the Mechanics laboratory in the A block of CIT. Testing was unfortunately not carried out under temperature-controlled conditions as described in ISO 37, however as the samples were stored together for over a week it is not expected that environmental factors played a large role in the results. It should be noted that it is only possible to compare the tensile properties of the 3D printed PVC parallel to the grain, as it is not possible to print such a thin and soft structure without being encased in support material.

Procedure

The machine was set up with a gauge length of 10mm and a strain rate of 100mm per minute. Samples were tightly clamped in the jaws of the machine in order to prevent sample slippage. Care was taken to ensure samples were correctly aligned in the machine, as pictured below:

Once the sample was firmly secured, the test was initiated.

Results

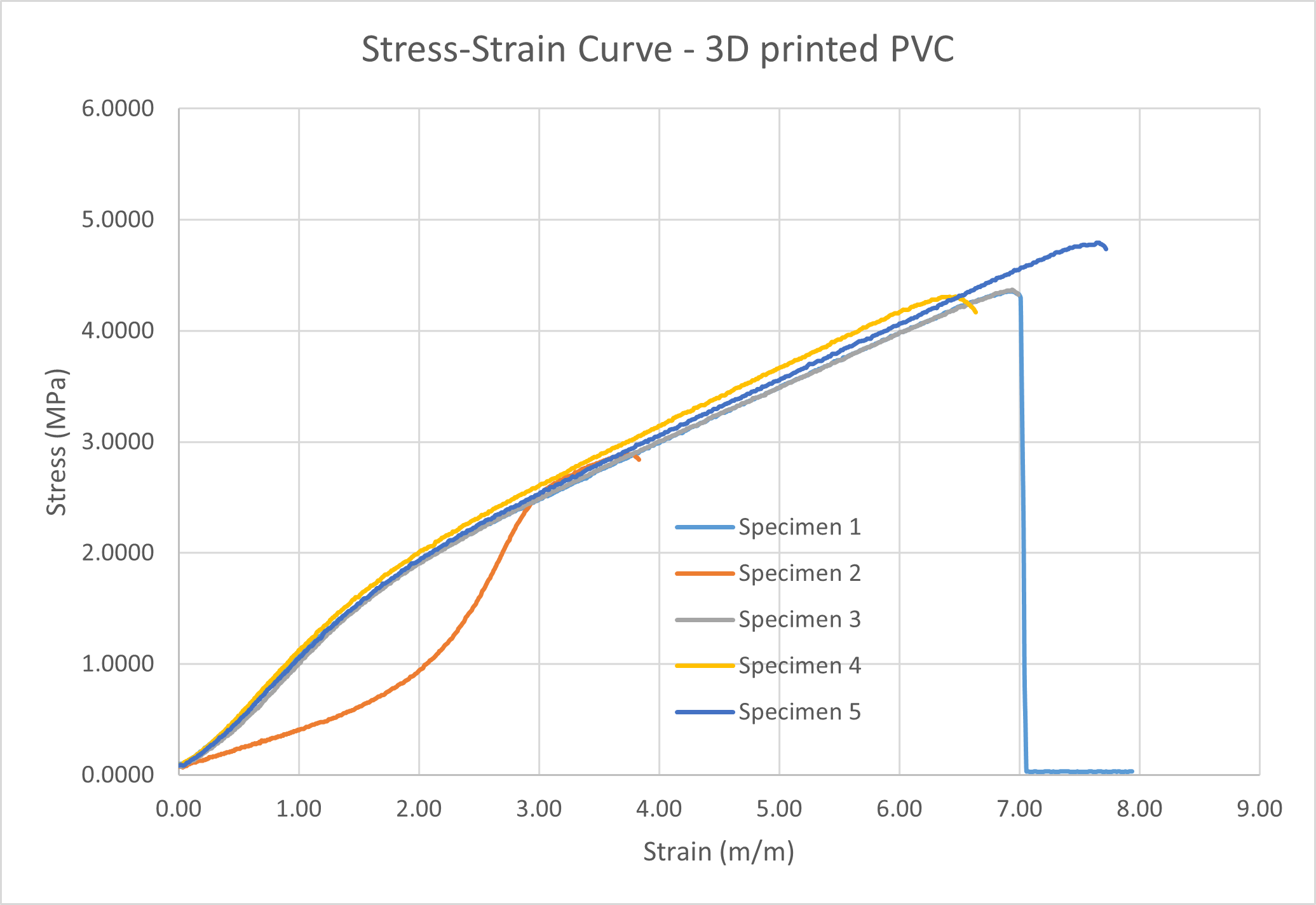

3D printed samples:

| Ultimate tensile strength (MPa) | Tensile strength at break (MPa) | Elongation at break (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specimen 1 | 4.3545 | 4.2955 | 600% |

| Specimen 2 | 2.8886 | 2.8409 | 283% |

| Specimen 3 | 4.3727 | 4.3273 | 599% |

| Specimen 4 | 4.3091 | 4.1682 | 564% |

| Specimen 5 | 4.7909 | 4.7341 | 672% |

| Average value | 4.1432 | 4.0732 | 544% |

| Standard deviation | 0.6509 | 0.6447 | 1.3487 |

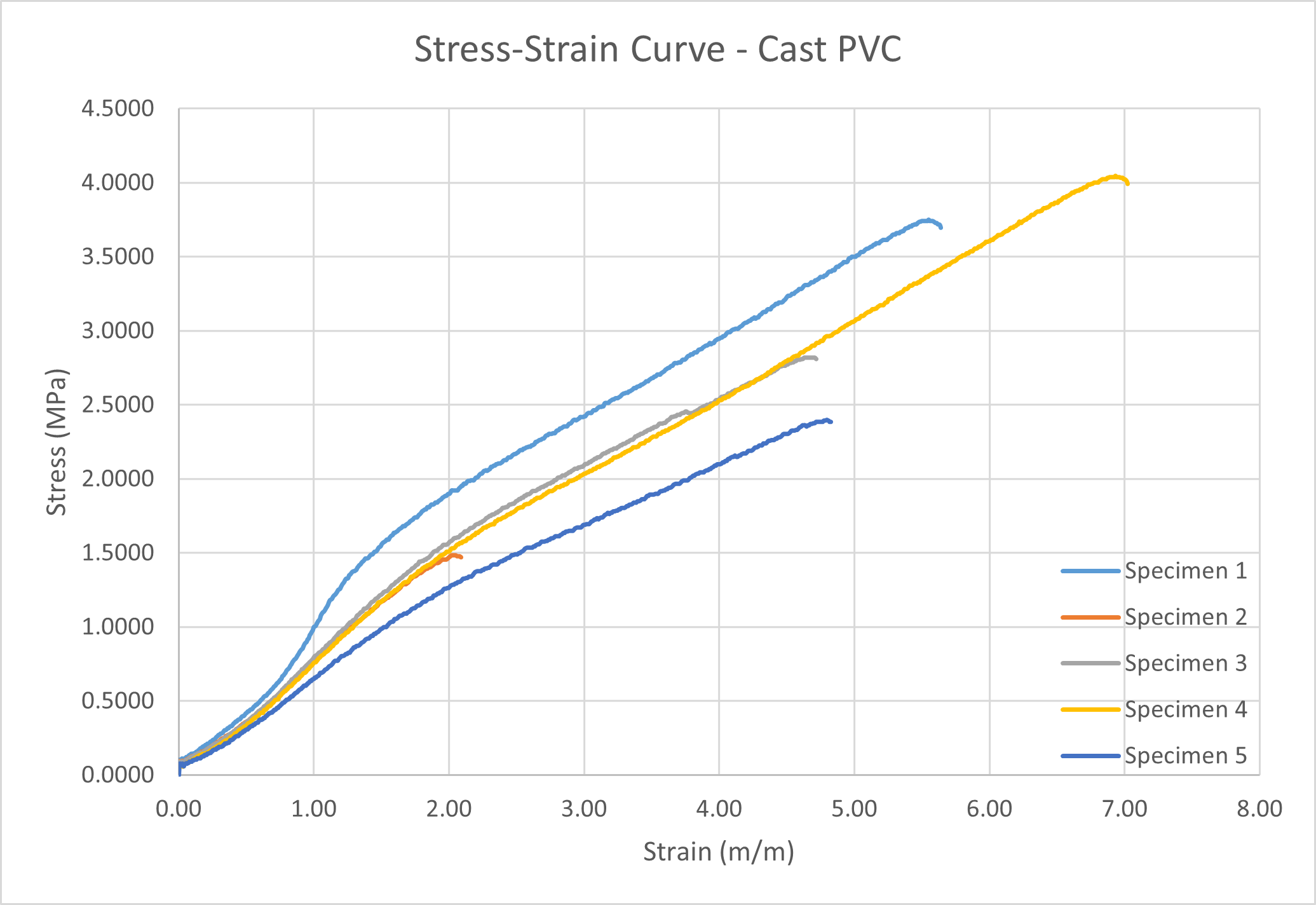

Cast samples

| Ultimate tensile strength (MPa) | Tensile strength at break (MPa) | Elongation at break (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specimen 1 | 3.7500 | 3.6955 | 464% |

| Specimen 2 | 1.4841 | 1.4705 | 109% |

| Specimen 3 | 2.8182 | 2.8091 | 372% |

| Specimen 4 | 4.0455 | 3.9909 | 602% |

| Specimen 5 | 2.4000 | 2.3864 | 386% |

| Average value | 2.8995 | 2.8705 | 387% |

| Standard deviation | 0.9269 | 0.9093 | 1.6104 |

Discussion of tensile testing results

Contrary to expectation, the 3D printed PVC proved to be about 43% stronger, both in ultimate tensile strength and in tensile strength at break. However, these results should be regarded with caution; firstly, these are very small sample sizes for an effective and statistically significant comparison, and secondly, the results contain some distorting factors. When the cast dumbbells were made, they were cast without a degassing step. This led to some of the samples being filled with bubbles and cavities, which negatively impact the mechanical properties of the samples. Furthermore, problems were encountered when clamping the samples in the tensile tester, as some samples slipped out from between the jaws of the clamp and had to be retested, which may damage the sample prior to retesting. Specimen 2 for example was strained almost to breaking, but slipped from the chuck of the machine. Retesting the sample gave a very low UTS and breaking strength when compared with the other samples.

All in all, these results are an interesting indicator, showing the possibility that the 3D printed PVC may actually have a significantly higher tensile strength than cast PVC.

Conclusion

Originally, this project was intended to achieve three major goals; The first goal, to examine the possibility of additive manufacturing with soft PVC was achieved in October of 2015 with the initial feasibility testing showing that PVC can be extruded through a common hot-end at pressures attainable by a 3D printer. The second goal, to integrate the feed system into a 3D printer and actually print with it was reached in late April with the production of a model of a human ear as well as a collection of test pieces to diagnose extrusion problems and material properties. Finally, the last goal has also been reached, if not quite conquered; it would have been much better to have had the time to produce and test large sample sizes to acquire statistically significant data, as well as being able to compare other material properties, particularly shore hardness.

Finally, I can say I regard this project as being enormously successful for myself; not only was the original idea proven to work, but I was able to access a wealth of knowledge in fields range from electronic design and mechanical design, to material science, chemistry, control theory, biology, CAD/CAM and biomedical manufacturing.